Photography in advertising

Patrick Rössler

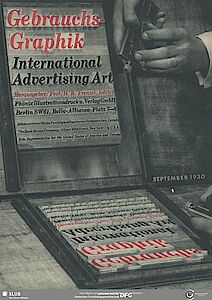

Photography was very much a part of modern advertising design in the late 1920s. As a result photographer’s portfolios were even then regularly featured in Gebrauchsgraphik. Almost incidentally therefore this publication did more than some photography magazines to foster the acceptance of »new photography«.

In the mid 1920s technological progress prompted real advances in visualisation options in modern mass communications: The advent of the 35 mm camera with reel film replaced the bulky plate camera, and powerful lenses and portable flashes meant it was possible to take photographs at times and in places that had previously remained undocumented. For this reason the everyday phenomenon of photography quickly became established in advertising design, too, because – as the avant-garde graphic artist Max Burchartz put it back in 1926 in Gebrauchsgraphik, »the photograph is objective to a great degree [...] when it is a matter of showing an objective, clearly recognisable image of any circumstances, then the photograph is always a suitable means.« Nevertheless, this »new form of seeing« remained alien to publisher Hermann Karl Frenzel for all his life, even though he did give »photography in advertising more space in our magazine« (GG 7/1927, p. 21). Here, too, he was in favour of a more moderate modern movement.

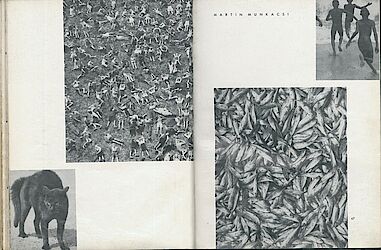

Unlike competing journals like the Swiss Typographische Monatsblätter, Gebrauchsgraphik never brought out a special issue on photography. But it did make a particular contribution in terms of the multi-page photographer’s portfolios it published, of prominent and less famous artists working in advertising or at least producing work that was adaptable for advertising purposes. At times these were self-taught photographers (like Sasha Stone) and – more often – illustrative journalists (e.g. Martin Munkácsi) or artists (like Man Ray). Only in a few cases were they professional photographers, such as the studio ringl + pit (Ellen Rosenberg and Grete Stern). Nowadays, the importance of these portfolios can hardly be overestimated: In a confusing market, in which monographs of photographic works could be counted on the fingers of one hand and in which anthologies such as the annual »Das deutsche Lichtbild« were fighting for recognition, the opulent photographic presentations in Gebrauchsgraphik were for many ateliers the only way of attractively presenting what they could do to potential clients.

One particularly successful presentation was of the work of the popular fashion photographer George Hoyningen-Huené, who exceptionally benefited from a dedicated gravure-printed supplement in rich blacks and with an enviable tonality (GG 2/1932). The fact that this on-staff photographer of Vogue had acquired his technical skills »in the American School«, shows once again the international orientation of Gebrauchsgraphik in this field, too. Before that, the magazine had also honoured the work of the American doyen of fashion photography, Edward J. Steichen (GG 1/1931). To Frenzel, it was irrelevant whether the photographer was »a Russian, a Frenchman or an American«; at the same time the attention paid to the fashion section also underlines the breadth of photographic positions in the magazine, all of them being categorised by the publisher simply as »modern« (GG 7/1931, p. 30).

It is indeed a difficult undertaking to pick out just one or two portfolios from such an illustrious collection. Representatives of the avant-garde that cropped up individually (e.g. John Heartfield, El Lissitzky and Herbert Bayer) are to be dealt with in more detail in the third part of this series; for that reason the example we are taking in this part are the double-page spreads dedicated to the work of Swiss New-Realist photographer Hans Finsler, the Jewish portraitist Yva (Else Neuländer) and the early Bauhaus photographers Mila and Hanns Hoffmann-Lederer.

On fifteen pages in the April 1931 issue, Gebrauchsgraphik published fifteen different works by Hans Finsler, described in the accompanying text as a »real expert«, and a »photographer and artist«. Finsler had been working at the Burg Giebichenstein college of arts and crafts in Halle since 1922, and he had played a large part in the Werkbund exhibition »Film und Foto« in 1929 in Stuttgart. In 1931, when his portfolio was published in Gebrauchsgraphik he was on the move to Zurich, where he was to work at the arts and crafts college there. The opulent presentation of his close-up photographs of confectionery and textile samples was certainly helpful for the opening of his Zurich-based atelier of object and advertising photography, as also were the featured photos that he had produced for the State Porcelain Manufactory in Berlin. »Finsler creates poems with the camera,« is how Eberhard Hölscher ended his write-up, and four years later, other motifs by Finsler were published (in an article on Swiss photography), this time less suited to advertising, such as the one of a sleeping elderly woman on a park bench in Paris, a true Finsler classic. This example shows very nicely that Frenzel was indeed at pains to present the diversity in the work of the photographers and therefore to honour their professional approach.

For the city of Magdeburg Hanns Hoffmann and his wife Mila Lederer had developed (amongst other things) the design of the municipal printed material, before setting up their own atelier in Berlin, which was then also involved in work for the trade show and exhibitions department of the city. The Gebrauchsgraphik portfolio from September 1930 shows in a virtually prototypical way both photographs as well as adverts; in the view of publisher Frenzel, these »advertising graphics which include self-produced photographs« show »the best graphic understanding and advertising and technical expertise«. Admitted, it is remarkable that Frenzel seems not to have considered it worth mentioning that both of them had worked at the Bauhaus school for a long time and had worked on the new building in Dessau, nor that they had had close contact with Johannes Itten and Oskar Schlemmer.

Finally, the busy Berlin-based society portraitist Else Neuländer, whose studio Yva was one of the most distinctive photo producers of the age, was most certainly already well known to the readership of Gebrauchsgraphik from other publications. She delivered photo stories as commissioned work to high-circulation magazines such as Ullstein’s Uhu and her evocative photos of film stars and society ladies were regularly printed in the press as whole-page decorative pictures. Of the thirteen photographs that accompanied the article on fashion journalist Margit von Plato, later wife of the architect Hans Scharoun, (GG 11/1931), there were also many less well-known advertising and object photographs by Yva. Later, in its advertising section, Gebrauchsgraphik even contained a real photo from Yva, stuck into the magazine: In the November issue of 1935 the graphic workshops of Gerhard & Teltow, Leipzig, advertised high-quality labels which they had applied as an example to a product shot by Yva.

Ironically Gebrauchsgraphik seldom used photographs to advertise for itself. Its covers were dominated by the – always drawn or painted – illustration in the classical sense. For this reason any photographs attracted particular attention, such as the combination of type and image in the America issue of October 1926, with a life-like lobster drawing attention to the show of colour photography (GG 6/1935), or in February 1940, in the midst of war, a sophisticated photograph of a nude model from the photo atelier of Deutscher Verlag, a publishing house aligned closely with the government. But its very first photographic cover turned out to be perhaps the most innovative ever – when Fritz Lewy stacked up urban industrial motifs into a wild cityscape scene for the August 1926 special issue on the Rhine-Ruhr district, referring not coincidentally to the famous »Metropolis« photomontages of the ex-Bauhaus artist Paul Citroën. But this seems again to be almost too much avant-garde for a magazine of the graphic mainstream, for at the end of 1932 Frenzel proclaimed, in his introduction to a monograph of the work of Hoyningen-Huené, that this »new way of seeing« was now over as an »experiment« and that it was now time to turn to the »propagandistic photographic art«.